Treasure/map

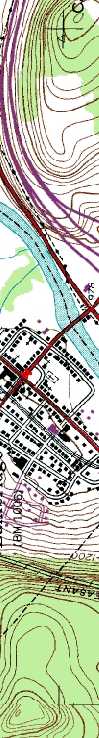

It probably still stands in the corner of the "Scout House" in my hometown, 40 years dustier and that much more marked up by identifying fingers and the odd, illegal, pencil -- a tall, framed board displaying nine 1919 series topographic maps of the Susquehanna valley and its neighborhood, neatly trimmed and glued in place. When I first saw it and realized what it was, it gave me a thrill like no other map has done since.

I was 11.

Now you're shaking your head and thinking, "what a geek! Thrilled by a map?"

But I was a kid with a great deal of imagination -- still am, I suppose -- and I was just spreading my wings in my little town. I had permission to roam a little farther every year, and I was learning to find my way around town alone, to explore the creek and drop stones on waterbugs under the river bridge, to heave my bike to the highest street and speed down to the first stop sign, and I was already beginning to wonder, "what else is there?"

Kids don't get that much freedom anymore, I don't think. Will I trust my first-grader to hike to school alone in a couple of years? In third grade, I walked clear across town, such as it was -- my parents felt safer and no one pestered them with warnings all the time.

I knew about topographic maps, and maps in general, from family trips. I'm sure I met road maps early -- I can't remember the first -- but I grasped the trick of squiggly contour lines from studying a map of my grandfather's that showed the Canadian lake where his cottage was. I loved that place, and I admired the map's pale green contour lines and light-blue water. For some reason, I don't remember the shape of the lake, but I do remember clearly the texture of the linen the map was printed on, and the pencil lines my grandfather drew to mark the compass bearings for boating from the "lower lake" to his cottage.

The map in the Scout House was a dark khaki, the color of the oldest Boy Scout uniforms, and it fascinated me because it showed me not three but four dimensions of my hometown.

There were the dense clusters of lines, just blocks from home, where an undiscovered gorge followed the route of Newton Brook. There were miles of unexplored country beyond, where forgotten placenames like Kelly's Corners and Yaleville beckoned -- and, I realized, there was history.

I could see the road west from town wasn't the same as the one I biked on. Another highway, north and east, had radically changed, too. Some of my friends' houses weren't marked on this map. There were sawmills, soil mines, and big, irregular dark buildings along the railroad tracks. Even in a town where history stares you in the face on every stroll, here was revelation.

So, of course, I explored. West Main Street had moved uphill because the old route had fallen into Newton Brook ages ago. I found the collapsed bank and a lovely picnic spot hidden under a white pine tree below it. With friends, I probed the old factories -- not long before they were torn down. I hiked up to some of the old houses and found forgotten foundations, and in one dooryard, a lilac tree that still thrived, long after the door it graced was gone.

I am still a map fan. Most of the time they inspire fantasies rather than explorations, though.

(Not everybody is comfortable with maps, I realize. Some women I know

give precise, accurate directions and follow them unfailingly, but want

nothing to do with pictures. Deep in North Carolina this summer, I met

a woman asking if "highway 25" would take her around Charlotte

to I-95. Darned if I know, I said, but probably not. I walked about 50

feet to a posted map, checked and ran back to advise the woman -- a friendly

person in her 60s -- to stick to the main road and avoid shortcuts. I

hope she got where she was going. Maybe she likes asking directions, the

way so many men don't.)

I am baffled myself by sky maps -- I can never get them

oriented correctly upside down, but I love the fantasy they give me of

standing outside listening to the racket of the crickets and frogs, feeling

the cool summer air and scanning the dark horizon for Bootes or the Pleiades.

Only recently I found out how a Polynesian sea chart worked, and I love

the fantasy (the opposite of the sky- map

one) that the chart inspires -- of listening to the water slap on the

side of my canoe and squinting toward the horizon to judge the prevailing

wind and the pattern of the waves.

map

one) that the chart inspires -- of listening to the water slap on the

side of my canoe and squinting toward the horizon to judge the prevailing

wind and the pattern of the waves.